CASSANDRA LANE was eleven years old when she told her mother she wanted to be a writer—but she added that she wanted to be "behind the scenes." Well, she's not behind the scenes anymore. Her debut memoir, We Are Bridges, was published in April of 2021 by Feminist Press. In it, she writes

Memory is a woman. Subtle, haunting, devastating. Right even when she is wrong.

We Are Bridges begins with the cover illustration by Krystal Quiles of what I imagine to be memories we hold inside us. When we open the book, we're reading a dream and a reality. Or as Cassandra writes, "a romance and a horror, a memoir and a fiction--forged out of what is known and what is unknown."

This is a story of family and memory—of what Cassandra remembers and of what other family members remember, and tell her. And when memory fails, imagination takes over. And yes, let it take over now before another layer is forgotten and while some facts exist to light its way.

When I dream of Mary, she is a young girl, not the old woman I once knew.

When Cassandra first felt the need to discover more about her family, she was in her early thirties attending a family reunion in her hometown. She wanted

to erase the distance between us, the years, the laws of physics and of man—just papery things really... Scientists say we are not matter but energy. A sheet of paper turns out to be a magic carpet after all, so I hop on, riding its electric waves through time.

Here was her starting point: Her great-grandfather Burt Bridges was lynched in 1904. Her great-grandmother Mary Magdalene Magee (McGee) was pregnant with her grandfather at the time.

Five years after that family reunion, when Cassandra became pregnant—something she'd sworn at sixteen she would never be—with a redemptive symmetry, she began to write the story of her great-grandparents. She wanted to be able to say who their family was and how it came into being.

Reading the memoir, we learn that Cassandra’s mother had five children and not enough money, and that when Cassandra became pregnant at just shy of her seventeenth birthday, she had an abortion. One of the things I love about this book is how well language is able to capture the family ties. Take a look at this sentence where you can feel the connections in the words themselves.

And so I, her quietly obstinate firstborn, held her just-out-of-the-womb lastborn mere weeks after I had aborted what would have been her firstborn grandchild.

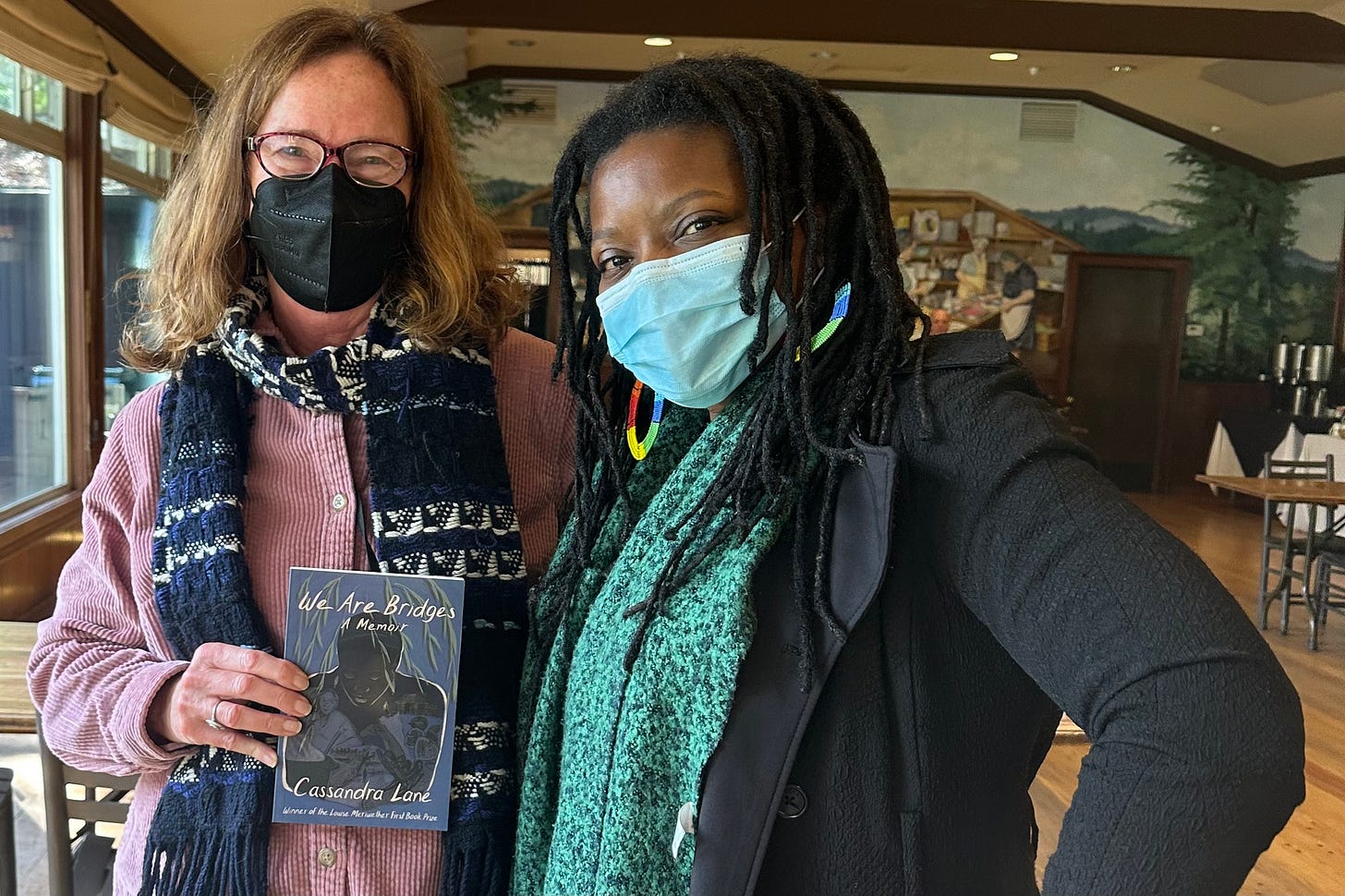

This memoir takes the only available facts and weaves a story that's the closest thing to truth that exists. As Martha Anne Toll wrote for NPR, "With this debut volume, Lane has written Burt Bridges into history. We Are Bridges makes a stunning contribution to what must become our collective memory." We Are Bridges won the 2020 Louise Meriwether First Book Prize.

Cassandra was born and raised in Louisiana. In college she studied journalism, and when she told her mother she was going to be a journalist, her mother said, "How are you going to be a journalist? You don't... talk to people." She became the first Black and first woman editor-in-chief of the campus newspaper. In 2001, she moved from Louisiana to Los Angeles to get her MFA in Creative Writing at Antioch University. After graduating, she taught journalism, literature, and composition at high schools in Highland Park and South L.A. She has also worked as a college applications advisor, senior writer for an education non-profit, and community relations manager for the Dodgers. She is currently editor in chief of L.A. Parent magazine. In 2017, her story on motherhood was chosen as part of the New York Times's series Conception: Six Stories of Becoming a Mother.

Come back on FEBRUARY 1st to read how CASSANDRA LANE spends her days.

Cassandra Lane and her memoir both sound fascinating. Thank you for highlighting her on How We Spend Our Days. As the child of an Indigenous dad and a white mom, I have questions similar to Cassandra's about what happened to the Indigenous side of my family. Her search for information, and her frank portrayal of her path to motherhood, both interest me because we are in danger of losing not just our abortion rights, but even the language of a chosen abortion she writes as, "And so I, her quietly obstinate firstborn, held her just-out-of-the-womb lastborn mere weeks after I had aborted what would have been her firstborn grandchild." As an obstinate third born who chose not to have children, I honor her choices at seventeen and later, and am curious to know more.