The dogs wake me at five. Late spring air smells sweet, coming through the open windows, and it’s just light. My spouse is still asleep so I get up quietly, let the dogs out, grab tea and my journal. I have journaled every morning since I was eighteen, in masses of unlined notebooks, covers often collaged from photos I feel inspired by. Today’s journal has garden pictures to celebrate the season we’re newly in.

Journaling and a half hour for my spiritual practice, the dogs at my feet, trying to be patient, and my day’s begun. I find my gear—leggings, a tank top, a fleece, socks, and Merrell walking shoes. An apple in one pocket, my phone in another, and I’m out the door.

I walk every morning, in almost any weather. Our home sits on farmland in the Monadnock mountain area of southern New Hampshire. Behind our house is land trust property. My walk starts downhill on our country road then it turns up a steep path that leads to the campus of a local arts school. If I’m sleep-deprived, I need distraction on the hill, so I use the time to scroll my Substack feed, read posts on writing, or listen to a UK podcast on animal communication that I’ve subscribed to. The top of the hill is finally in sight. I pause, stretch, enjoy the view, eat my apple, then start back down. This is when my thoughts turn to the writing day ahead.

But when I get home, at this time of year I don’t go to my writing right away. The sun is fully up, the garden awash with light. I open the greenhouse first—it’s small but enough for early lettuce and kales, summer vegetables later, more greens in fall. I water everything. Next is the small orchard, about fifteen fruit trees. They’ve bloomed well this year; we may get a bounty of peaches, pears, even plums. I wander along the paths of the perennial garden and pick flowers, then visit the raised beds in the vegetable garden and gather a handful of asparagus for breakfast. Say hello to the bluebirds nesting in one of the blue-painted wooden birdhouses and orioles at the new feeder—they are migrating through, and we caught them hungry. I feel like May Sarton in her Journal of a Solitude—a daily practice of garden wandering, then words.

The dogs are waiting at the door when I get inside. I feed them then make our breakfast: scrambled eggs, sweet onions, and asparagus I just picked. I started my writing life as a food journalist with a weekly column for the Los Angeles Times syndicate, and cooking is still a passion. My spouse is up, we share breakfast, talk about our day.

I often garden for a few more hours before I write. Morning is my favorite time, the air is still fresh and cool, and the ideas I’ve begun working out on my walk get a chance to percolate.

Today I am revising one of the perennial beds, making a new path through an overgrown section. It’s unforgiving, heavy work for my aging body—digging up masses of roots and transporting this “flower” sod to an emptier area, then lining the new path with landscape fabric and mulch. It takes an hour or more, I get very dirty and sweaty, and I’m well content. The dogs join me, sleep in the spring sun.

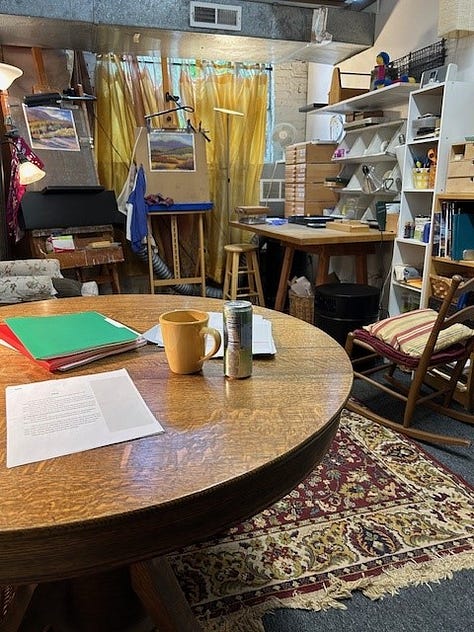

I clean up and pack a lunch to take to the art and writing space my spouse and I share in a large brick building in our mill town. It was once a mop factory, now converted to artists’ studios. The studio is just ten minutes away. It’s large, with a loft. Half of it holds my two easels and painting supplies. Half my writing table and desk.

I’ve always toggled art forms. I paint in the summer, mostly outside, and write in the winter, inside. When we rented the studio twelve years ago, I saw how it could house both my writing and my painting so I could do everything year-round.

Today I’m working on revision at my desk too: I’m finalizing the order of a new collection of short stories I’ve worked on for ten years. Short stories are a different challenge than the three novels I’ve published. I can accumulate ideas that don’t fit a longer work. I take classes during dry times to stretch my creative muscles. The round oak table that serves as my desk is stacked with folders of stories in progress, nearly forty at different stages. Ten are published in lit magazines, most have been workshopped with writing group or colleagues, some are just a title and an idea.

I start my writing time by reading: a few pages from a published short-story collection I’m studying, notes from my last writing session, plans for today’s. I’m fascinated with how other writers curate their collections. I have so many questions as a novelist entering a completely new genre: What belongs in a good collection? How many stories? Do they have to link? Some collections I read feel so random—do I want that? What might be a theme for my stories? How do I order and segue between them?

This has been my work for the past six months, since my third novel was released. Promotion is grueling for me—podcasts and interviews and social media, saying yes to every opportunity. I don’t write much beyond journaling during those times. After a long break, these stories began calling to me, even though I have an idea for another novel. I needed the freedom of short form as my brain recovered. I found my story folders, read through all the drafts, and selected fifteen that might work together in a book. As I worked through them, I did begin to see a running theme: women’s heartbreak and how it can heal unexpectedly. I like the idea of offering light to today’s world, while being honest about brokenness.

We share our mill building with a ceramicist, a jewelry designer, and a woodworker, but their studios are quiet today and I’m able to concentrate. I set out my revision notes for two flash stories in the collection that need the most work. Unpack my lunch and get a can of San Pelligrino from the little fridge. Set my phone alarm for two hours, what I can manage in one stretch before I have to move.

I start a revision list for each of the stories, writing by hand on a notepad, considering comments from the last workshopping session.

I work intuitively when revising but also linearly, using a list method adapted from Robert Boswell’s The Half-Known World and his idea of transitional drafts. Each revision opens more opportunities for the stories. My list is triaged into levels of difficulty: more research required, a problem I can’t easily solve, a lot of rearranging of other parts as a result of this possible change. Boswell suggests starting with the smallest changes on the list; I find it builds confidence in my revision process. Today there are timeline glitches I can easily fix, so I begin there. An hour passes. I get warmed up enough to consider larger story problems.

My alarm pings. I’m ready to move.

I save my file, sleep my computer, set the phone alarm for another hour, and head to my two easels. I’m revising there too, two “starts” made in the field, en plein air, landscapes from a trip to Tucson. On the table beside my easels are drawers with my colors—I paint in soft pastels, essentially compressed oil paints without the medium—and I have hundreds.

It’s a relief to work with colors, spatial relationships, tactile movements of hand and eye after staring at a small computer screen for two hours. As I paint, as my body moves, I let the story problems simmer and listen for ideas, solutions, a new perspective on the writing.

Revising a painting is so different from revising a story, though. I have steps but I leap into the intuitive much faster. I know to work from back to front, background to foreground, correcting everything from perspective to color choice to shape. But it’s as easy to lose myself as I did with the writing revision. One idea leads to the next.

When the phone alarm pings again, I step away and see what I’ve managed to do. Sometimes, it’s not an improvement; sometimes I can’t even work a full hour before the story calls me back. Sometimes it’s a magical relief to be immersed in color. I manage an hour today, fairly satisfied.

I clean up, make some notes for the next day’s writing work, pack my laptop and story folders, put away painting supplies, and head home. It’s almost time for dinner. The dogs are waiting. They get a walk, a little more time outside while I close the greenhouse for the night.

When I worked full time as a writing teacher and editor, when I was in production of books or marketing them, I had nothing like the luxury of time I had today. Now there is so much freedom. Our son is grown and living on his own, we are both newly retired, we can devote ourselves to creative lives. Evenings are relaxed and open, whatever we have energy for. Friends may come for dinner, we may watch a movie, or we may read. Tonight the air is warm, and we decide to take our books out on the screened porch, have dinner, and read until dark. I make a curry from leftovers. We watch the light fade.

THE NEW SAME 3 QUESTIONS…

1. What one word best describes your writing life?

Immersive.

2. Is there a book you’ve read over and over again?

I have so many. In summer, I give myself a pile of favorites to reread. One that always makes the stack is Peter Heller’s debut thriller, The Dog Stars.

3. What is your strangest obsession or habit?

I can’t create in a messy environment. I’m a visual person, and disorder short-circuits my brain. I have to have a clean desk (and computer desktop) to start work. I can make a mess while I’m creating, but I have to clean it up before I can start again the next day. This is very odd for a painter—most visual artists I know have delightful chaos in their studios. Maybe less odd for a writer.

This detailed, sensory showing of your creation process is fascinating and instructional to me. I have a similar, but not as deep, branching, and aware process as yours. I have followed you for years and learned so very very much. Thank you in ways I am beginning to understand,

Joyful and re-inspired by your passion for art and writing, your love of nature and gardening…. Every word, thought, and musing touches my heart with full emotion of being understood. Thank you, Mary. So much I have started, now completion seems hopeful, even though great challenge and quick-change direction continually.

Ardi